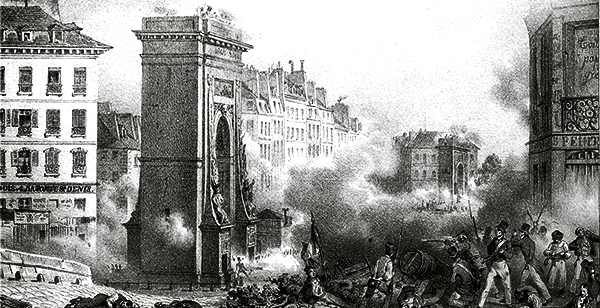

The Silent Boy wouldn’t have happened without Hilary Mantel. It was her brilliant novel about the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety, that inspired me to explore the period as a possible setting. But I needed a fresh approach to it.

The Silent Boy wouldn’t have happened without Hilary Mantel. It was her brilliant novel about the French Revolution, A Place of Greater Safety, that inspired me to explore the period as a possible setting. But I needed a fresh approach to it.

I also wanted to see more of Edward Savill, the flawed civil servant of my previous novel, The Scent of Death, which is set in New York during the American War of Independence. I liked the idea of following him back to Europe, and seeing how he was coping twelve years later, and how another revolution affected him.

As for a plot, all I had was the idea that Savill’s estranged wife, who had been in the background of the earlier book, might have ended up in Paris; that she might have died there, leaving problems for her husband to sort out.

I wrote a few thousand words but the story failed to catch fire. Then I had the idea that Savill’s wife might have left a son behind, father unknown. Still the book wouldn’t work. Then the breakthrough came from a completely different direction.

For other reasons, I had been researching post-traumatic stress. I discovered that ‘elective mutism’ can be one of the symptoms. What if this boy were mute – not from birth, but because of something he had seen or done. The Silent Boy, I wrote in my notebook.

Something still wasn’t right. The book only began to come alive when I stopped trying to construct a plot and started writing from the viewpoint of the silent boy himself. The first words I wrote were:

‘On Tuesdays, the boy comes for the washing.’

Suddenly I was in the middle of the story, looking out at the world, rather than stuck outside trying to peer in. The boy was called Charles and he was desperately trying to keep himself sane. The question that drives the story then became: what would Charles say if he could speak? (Almost everyone else in the novel is desperate to know the answer.) I also felt immensely sorry for Charles. In a sense, that’s what kept me writing.

Mutism was seen very differently in 1792. Only a hundred years earlier, one ‘expert’ had argued that mutes were subhuman – for, without the power of speech, how could they pray to God? During the eighteenth century, some thinkers who studied the phenomenon thought that dumb people were unable to develop a moral sense. Toward the end of the eighteenth century, doctors found other ways of looking at the condition. Many of their treatments seem shockingly inhumane to us today.

For me, this book will always be the story of a small, terrified, silent boy. But perhaps it has a wider theme, one that I’ve only realised now: that, for all its achievements, science without humanity and a sense of its own shortcomings can be worse than no science at all.

The Silent Boy is the Times, Sunday Times & Radio 4 Historical Crime Novel of the Year. It currently available in hardback and releases in paperback Thursday, February 26th.